One of the most commonly heard phrases in a school principal’s office is, “I didn’t do it”, second only to, “It wasn’t me”. Teaching children to take ownership of their actions so that they can take the steps necessary to make amends is no easy feat. We are asking children to admit they are wrong, something that most adults are incapable of or unwilling to do. This stubborn approach to dealing with our mistakes, our transgressions, is easy to deal with when we are dealing with a child who drew on the freshly painted wall with a sharpie, or with broken shards of the antique vase lying atop a baseball, but as they say, bigger children, bigger problems. What of the mistakes we make as adults? How can we move past them? These have the potential to impact our careers, our relationships and in extreme cases, even our very lives.

This week’s parasha, Ki Tisa, describes one of the lowest points in the spiritual journey of the Jewish people: the sin of the Golden Calf (Shemot 30, 11-35). Bnei Israel, impatient for Moshe’s to return from Har Sinai, begin to wonder and worry that perhaps something happened to Moshe; perhaps he may never return, perhaps he is no longer even alive. Amidst this distress, the Eirev Rav, a group of former Egyptians who joined with the Israelites and became Jewish themselves, convince the rest of Bnei Israel that a new leader is needed. And, since no one is as holy as Moshe, and still embracing some of their former ways, they decide that the new leader should be an image to be served as an idol. The people then turn to Aharon and ask him to make the image for them.

Aharon faces a terrible dilemma. On the one hand, if he helps them, then at least he would maintain some control of the situation. On the other hand, if he refuses, his life would clearly be in imminent danger. Aharon had just witnessed the murder of Chur, son of Miriam and nephew of Moshe. Chur had spoken out to the people, he called for patience, and asked that they have faith that Moshe will soon return. But his pleas went unheeded and he was killed.

So, with a heavy heart, feeling that he has no choice, Aharon tells the people to ask their wives and children for all their jewelry and gold so that it can be melted down to create an image. According to Rashi, this was a delaying tactic; Aharon was hoping that the women or children would be reluctant to part with their precious jewels thus buying time for Moshe’s return. Despite his best efforts, gold was quickly collected and brought to him and it was not long before the Golden Calf was created.

Aharon tried again, this time suggesting that an altar be built to offer sacrifices to Hashem the next day. Maybe Moshe would return by then? Unfortunately, once again, the process did not take long. The people woke early the next morning and turned Aharon’s plans into a festival, complete with offerings to the Golden Calf.

As we all recall, the narrative goes on to describe Moshe’s return, his anger at the site of the people worshipping the Golden Calf and the subsequent breaking of the tablets. Following this incident, G-d punishes the people, striking them with a plague. Yet interestingly, Aharon, unaffected by the disease, goes on to serve as a high priest unpunished. Was he not guilty for having allowed, even facilitated the creation of the Golden Calf?

Chur himself was rewarded, albeit posthumously, as we would have expected, for having had the courage to stand up for what was right. G-d rewarded him by blessing his children: his grandson, Betzalel, becomes the builder of the Mishkan and the descendants of Chur became several Kings of Israel, including King David. How then, can the man who did not stand up for what was right, not only escape punishment, but also be rewarded by becoming high priest?

One opinion simply states that Aharon was punished, but that out of respect for the position of the Cohen Gadol, Aharon’s punishment is not mentioned.

Rashi suggests that Aharon’s motives were to spare his life and create a series of delaying tactics, as mentioned above. This in and of itself, is also problematic, as we are taught not to wait for miracles, and that essentially, G-d helps those who help themselves. The Gemara (Sanhedrin 7a) suggests that this was not really the case. After seeing what the people had done to Chur, Aharon wanted to spare them further punishment from G-d for killing a Cohen and a Navi; Aharon was therefore essentially trying to save the people from themselves.

Another possible explanation is that G-d needed Aharon, the High Priest, to be spared. According to Jewish law, the Cohen Gadol must be unblemished in order to act on behalf of the people. By sparing Aharon, G-d enabled him to ask for forgiveness on behalf of the people for their sin. Thus, Aharon was only spared from judgement in the immediate because G-d needed him and not because he deserved lesser punishment than everyone else. It should be noted that Aharon was indeed punished, almost in parallel to the rewards bestowed upon Chur: Aharon dies in the wilderness and never sees the Land of Israel. And, unlike Chur who was rewarded through his children, Aharon endures the loss of his adult sons, Nadab and Abihu.

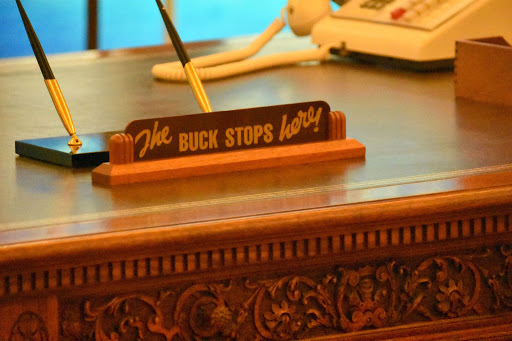

Someone once said that “if you never make mistakes, you never make anything”. We all, like Aharon, are merely human. We often make mistakes. Sometimes, even our best of intentions do not work out the way we planned, having long-term consequences we did not anticipate. But pleading our humanity is not an excuse. In the Rambam’s Steps to Repentance the first step is admitting the sin, the wrong-doing. Making excuses or attempting to justify our actions will not spare us from consequences. Taking ownership of our actions is the first step to making amends, regardless of the magnitude of the transgression.

Parashat Ki Tisa also states the thirteen attributes of mercy which we recite on fast days to show our gratitude for G-d’s mercy, most specifically, for not having destroyed the Jewish people. The power of repentance was able to save an entire nation. We have, within us, the power to change our destiny, to improve our lives for the better. But in order to walk that new path, we must first look down at our feet and see where they are planted, for better or for worse, and own up to where we stand.

Shabbat Shalom,

Dr. Laura Segall

Head of School